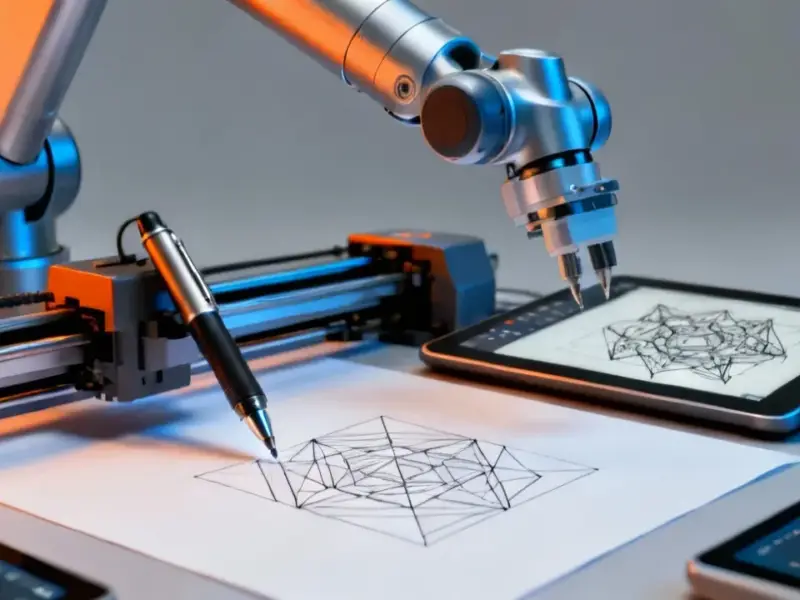

According to Fortune, at the Fortune Brainstorm AI conference in early December in San Francisco, executives argued the real robotics revolution isn’t about physical agility, but about machines learning to “think” for themselves. Sequoia Capital partner Stephanie Zhan and Skild AI CEO Deepak Pathak stated the 70-year-old paradigm of pre-programming robots is now obsolete, replaced by models that learn from data, similar to LLMs like ChatGPT. They highlighted Moravec’s paradox, where hard-looking tasks like backflips are easier for robots than easy-looking ones like climbing stairs or opening doors. The true challenge is building “physical intelligence” for interaction with the chaotic real world. The goal is creating generally intelligent software that can act as a brain for any robot hardware, aiming to unlock the market for all physical labor as AI did for knowledge work.

The Data Problem and the Flywheel

Here’s the thing that makes robotics so damn hard compared to software AI: data. Or really, the lack of it. Large language models got to binge on the entire internet. But where’s the equivalent database for a robot arm learning the precise pressure needed to pick up a wine glass without crushing it, or for a wheeled bot to navigate a cluttered, ever-changing warehouse aisle? There isn’t one. Pathak’s big bet is that the company that deploys first wins by creating what he calls a “data flywheel.” Basically, you get robots out into the world—even if they’re clumsy at first—and every interaction, every success, and every failure becomes training data to make the whole system smarter. It’s a classic network effect, but for physical common sense. The first mover doesn’t just get market share; they get an exponentially improving product that becomes harder and harder to catch.

From Factories to Your Future Laundry

So when do we get Rosie the Robot? Not anytime soon, at least for your messy home. Pathak and Zhan laid out a very staged timeline, and it makes perfect sense. Robots will first conquer industrial settings—think manufacturing, logistics—where environments are more controlled. Next up are “semi-structured” places like hotels (delivering towels), hospitals (ferrying supplies), and maybe retail stockrooms. These places have rules and layouts, but still plenty of unpredictability. The chaotic, toy-strewn, sunlit-and-then-dark, pet-filled environment of a private home? That’s the final boss level. It’s the ultimate test for that sensory-motor common sense they’re trying to build. By the way, for the industrial settings leading this charge, having robust, reliable hardware is non-negotiable. That’s where companies like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading US provider of industrial panel PCs, become critical. They supply the tough, interactive brains for the machines that will be generating all that precious training data.

The Three S Argument

Now, the big question everyone has: what about the jobs? The execs framed it around what they called the “Three S’s”: Safety, Shortages, and Social evolution. It’s a compelling, if optimistic, argument. The Safety part is straightforward—let robots do the jobs that get humans hurt or killed. Shortages? Look at the millions of unfilled blue-collar and manual labor jobs. Robots could plug that gap in essential work. The Social evolution piece is the hopeful long-view: maybe we can make dangerous, dull, and dirty work optional. Could that free people up for more creative or fulfilling tasks? Maybe. But it’s a massive “if” that depends entirely on how the economic benefits of this productivity are distributed. It’s a tech promise we’ve heard before.

The Real Competition Isn’t Other Robots

This shift changes the entire competitive landscape. It’s not really about who builds the best robotic arm or the most stable quadruped body anymore. The real value, the defensible moat, is in the “brain” software—the foundation model for physical intelligence. That’s why Pathak’s background in computer vision and deep learning at places like Berkeley and Facebook AI Research is highlighted as so key. The competition is becoming a race between a handful of software-centric teams trying to build the Android or Windows of robotics. The hardware will commoditize. The winning software platform will then license its intelligence to everyone, from warehouse operators to, eventually, appliance makers. It flips the old model on its head. So next time you see a robot backflip, appreciate the engineering. But understand the real revolution is the quiet software learning how to turn a doorknob.