According to SciTechDaily, researchers at The Rockefeller University have used cryo-electron microscopy to uncover a hidden “jack-in-the-box” activation mechanism inside the T cell receptor (TCR), a protein complex central to all cancer immunotherapies. The team, led by first author Ryan Notti and senior author Thomas Walz, published the findings on December 16, 2025, in Nature Communications. By placing the TCR into a custom nanodisc that mimics its native membrane environment—a first for this complex—they captured it in a closed, dormant state. The images show the receptor physically springs open and extends outward when activated by an antigen, a conformational change earlier studies in detergent had completely missed. This fundamental discovery provides a new structural blueprint that could help re-engineer the next generation of T cell therapies and vaccines.

Why This Breakthrough Matters

Here’s the thing: we’ve been using T cell immunotherapies for years with incredible, sometimes curative, success in certain cancers. But we’ve basically been flying partially blind. As Walz put it, it’s “remarkable that we use the system but really have had no idea how it actually works.” That knowledge gap is a huge problem when you consider that these therapies fail for most cancers. Notti, who treats sarcoma patients, was motivated by exactly that frustration—seeing patients who couldn’t benefit. So, nailing down the very first physical step of activation isn’t just academic. It’s the missing manual for a tool we already have, and it could be the key to tuning it for wider use.

The Membrane Is Everything

The real genius of this work was in the setup. Previous structural studies dissolved the cell membrane with detergent to isolate the TCR. But that’s like studying a mousetrap after you’ve already sprung it. Walz’s lab specializes in recreating custom membrane environments. They built a nanodisc with the exact lipid mixture found in a real T cell membrane, and only then did they insert the full, eight-protein TCR complex. That intact membrane acted like the closed lid on the jack-in-the-box, holding the receptor in its compact, ready state. The moment they saw that closed structure in the cryo-EM data, they knew they’d overturned the old model. It turns out the native membrane isn’t just a backdrop; it’s an essential, stabilizing component of the switch itself.

What This Means For Future Therapies

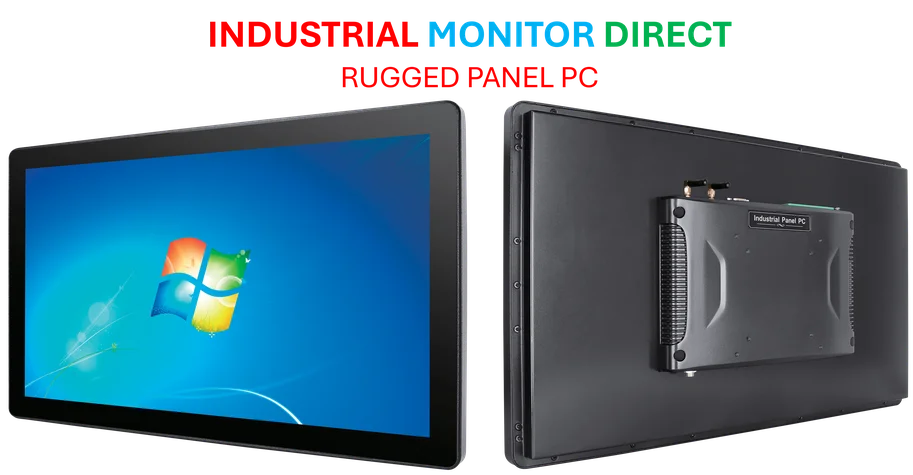

So what can you actually do with this new picture? The implications are pretty direct for bio-engineering. Now that scientists know the receptor has a specific closed-to-open physical motion, they can start to ask new questions. Can we design synthetic receptors that spring open more easily, making T cells hypersensitive to weaker cancer signals? Or, conversely, can we engineer receptors that are harder to trigger, to avoid dangerous overreactions and side effects? Notti mentions tuning the “activation threshold,” and that’s exactly the kind of precise control this enables. It also opens new doors for vaccine design, giving a clearer view of how antigens and receptors interact. This is basic science, but it’s the kind that directly feeds the applied engineering pipeline. For industries that depend on precise biological control, like advanced therapeutics, this level of insight is gold. It’s similar to how having exact schematics allows for better engineering in any field, whether it’s a delicate protein complex or a robust industrial panel PC built for harsh environments—precision understanding leads to better, more reliable performance.

A New Era of Precision

Look, this doesn’t mean a new cancer cure drops tomorrow. Science doesn’t work that way. But it does mark a pivotal shift from guessing to knowing. For decades, immunotherapy development involved a lot of trial and error at this fundamental level. Now, there’s a high-resolution target. The next steps will involve using this structure to model thousands of interactions, to design and test new receptor variants, and to finally understand why some antigens trigger a response and others don’t. It transforms a black box into a transparent, manipulable machine. And in the long fight against cancer, that’s not just progress—it’s a whole new playbook.