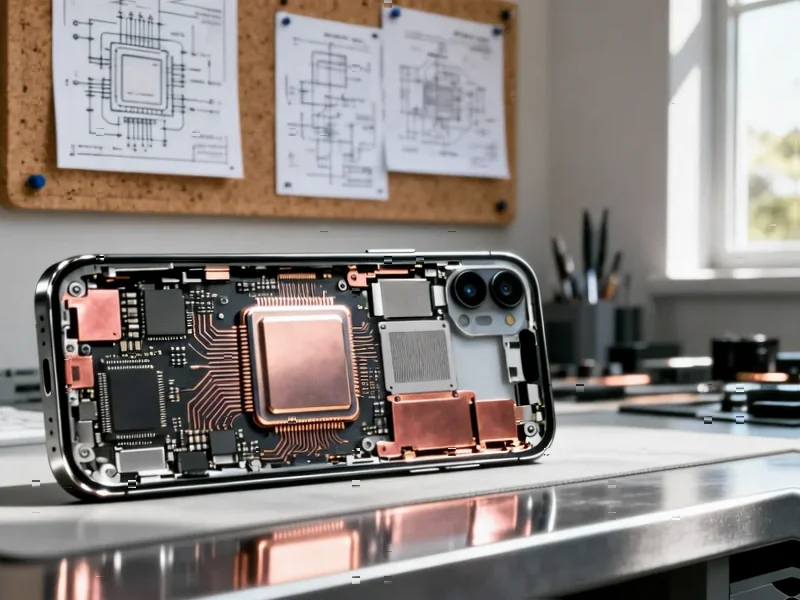

According to SamMobile, Samsung’s Galaxy Z TriFold is a fascinating financial experiment. The device is priced at a precise 3,59,0400 won (about $2,500) in South Korea, a figure that suggests the company is either just breaking even or even losing money on each unit sold there. It’s only available in six markets—South Korea, the US, UAE, China, Singapore, and Taiwan—with prices soaring over $3,000 in the UAE. So far, Samsung has sold a mere 3,000 to 4,000 units, with total sales expected to cap at around 30,000. The company has avoided wide-scale media reviews and mass production, treating this more like a tightly controlled technology showcase than a traditional product launch.

Why lose money on a phone?

Here’s the thing: this isn’t a bad business decision. It’s a strategic one. Samsung‘s primary goal with the Z TriFold right now isn’t to make a profit. It’s to plant a flag. They want to prove to the world, and especially to investors and competitors, that they have the engineering chops to build a commercially available tri-fold phone—something no other major non-Chinese brand has done. By keeping the release extremely limited, they control the narrative, create an aura of exclusivity, and avoid the massive costs of a global marketing blitz and production ramp-up. Basically, they’re extracting maximum prestige from minimal volume.

The scarcity playbook

And it’s working. The device has sold out quickly in its limited markets, partly because Samsung is deliberately making so few of them. Contrast this with their mainstream foldables: the Galaxy Z Fold 7 and Flip 7 racked up over a million pre-orders. For a product like the TriFold, where component costs are sky-high and assembly is fiendishly complex, scaling up doesn’t make financial sense yet. Why ramp up production when the margins are terrible or non-existent? This controlled scarcity keeps demand perception high while Samsung figures out how to actually make the thing profitable down the line.

A market without real competition

Samsung can afford this slow-roll strategy because, frankly, who’s competing with them? Sure, there are tri-fold phones from Chinese manufacturers, but they aren’t available in key markets like the US. A device like Huawei’s Mate XT can’t offer full Google services, which is a deal-breaker for most premium buyers outside China. So Samsung owns this niche by default for now. They’re showcasing market leadership without the pressure of a real sales race. It’s a luxury most tech companies don’t have.

The long game for foldables

So what’s the endgame? Samsung absolutely wants to make a tri-fold a mass-market product eventually. But “eventually” is the key word. This first model is a proof-of-concept, a testbed for technology and consumer reaction. The real volume play might be a year or more away with a successor model. For now, they’re happy to let the Z TriFold be a spectacular, conversation-starting loss leader. It’s a marketing expense that demonstrates their R&D might, and in the high-stakes world of cutting-edge hardware, that brand capital can be worth more than immediate profit. It’s a reminder that in sectors pushing the envelope on form factors, from consumer devices to specialized industrial panel PCs, establishing technological leadership often requires planting flags before counting dollars.